Like most things these days, the quotidian act of going out for groceries suddenly feels like uncharted territory. Nowhere is this change more apparent than at the Park Slope Food Coop. Over its 47-year history, brownstone Brooklyn’s bastion of 1970s idealism has stayed remarkably resilient. But the coronavirus has shaken the community-minded store to its very foundation.

The most obvious change? The day after Governor Cuomo mandated that nonessential workers stay home, the co-op’s leadership suspended members’ mandatory work shifts for the first time ever, hiring 55 temporary employees to manage stocking, checkout, bulk-food packaging, and maintenance.

“We didn’t think the governor was suggesting that all of our 17,000 member-workers were essential,” said Ann Herpel, one of the co-op’s general coordinators. “And it wasn’t safe to expose our staff to so many extra people throughout the day.”

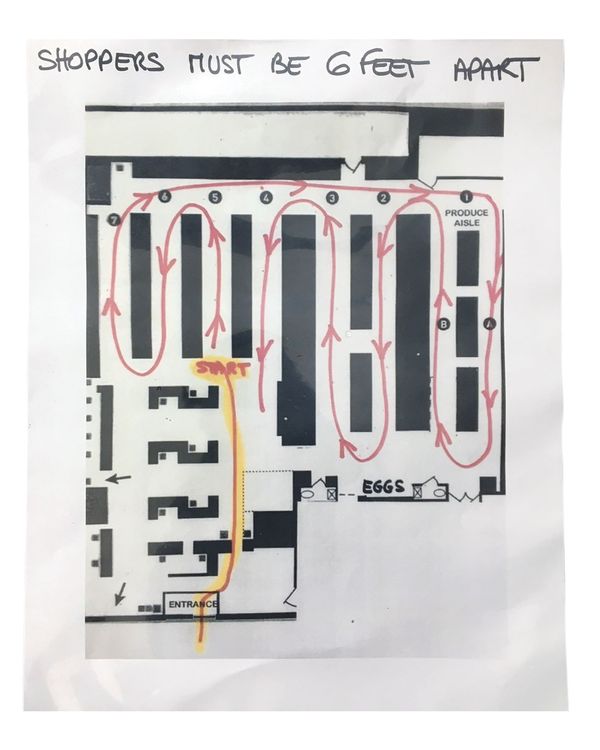

For a collectively run entity, where a decision as basic as whether to accept debit cards took seven years to pass through committees, the shift away from member labor was uncharacteristically swift and top down. Other changes feel equally drastic: A maximum of 35 shoppers at a time are now allowed in the 6,000-square-foot store, resulting in a socially distanced line outside that routinely snakes around the block. As at other stores, some hours have been limited to seniors and high-risk individuals (all day Thursday, in this case), plexiglass barriers have been erected at checkout stations, and the total number of shoppers in most aisles is capped at four. Still, members used to edging around one another to reach a bunch of organic bok choy or a bottle of Vermont maple syrup continue to drift closer than six feet despite best intentions. “It is only a jar of peanut butter,” Herpel said. “You can stand and wait a minute.”

But members of the Park Slope Food Coop (myself included), perhaps even more than most New Yorkers, are preternaturally disposed to closeness. In non-pandemic times, the place serves as a social hub as much as a grocery store: Friends hug and catch up, shoppers and workers swap recipe ideas, and the occasional passive-aggressive squabble breaks out in the checkout line. Unlike most grocery stores, where customers maintain a head-down, shop-buy-leave mentality, the coronavirus’s enforced physical separation threatens the co-op’s entire gestalt.

The biggest disruption has been financial. In the panic-stricken weeks leading up to New York’s stay-at-home measures, Herpel said sales were “extraordinarily high as members began to prepare.” The crowding conditions approached packed-subway-car-level severe even by cozy co-op standards.

But in a recent emergency memo to members, general manager and co-founder Joe Holtz wrote that since March 23, when the reduced-shopper rule went into effect, transactions have gone down by 80 percent (from approximately 2,400 daily transactions to just 380) and sales by 45 percent. This has resulted in a $500,000 loss in weekly sales revenue, which typically averaged over $1.1 million. At the same time, the temporary hires have increased overhead. “This is not a sustainable amount for running a cooperative that is this size,” Holtz wrote. “I have to expect that the social-distancing protocols will go on through mid-August. This means a significant drop in our financial liquidity … But what if it goes beyond mid-August?”

The fear of losing what for many members is both a communal and culinary lifeline has inspired a number of armchair recommendations on social media. Some have called for implementing delivery or curbside pickup, but Herpel said neither option is realistic. “If companies like FreshDirect are having trouble fulfilling increased customer orders, and delivery is their entire business model, why do people think the co-op could do it?” she said. “And where would all of those curbside groceries be stored until they were picked up? We are not miracle workers.”

Others have recommended that the co-op set up a GoFundMe or similar donation campaign. According to Herpel, the co-op is working with one of its cooperative banks on an online donation system. Until then, she said, members can mail in a check. “I know it is old-fashioned!” she said. On the more tech-savvy side, one member is developing software that allows people to schedule appointments to shop. This would ideally decrease wait times and (safely) maximize the number of shoppers cycling through during the currently curtailed operating hours. Meanwhile, members have taken to Instagram to report their waits in real time — an act that, in typical cooperative fashion, simultaneously allows them to air grievances and help others.

Herpel has plenty of hope the co-op can weather this most recent storm. “I don’t know what it will look like yet for people to feel comfortable coming back to do their work shifts. And I don’t know if we will ever be as crowded as before,” she said. “But there are a tremendous number of people for whom the co-op is essential to their lives, and there is a tremendous amount of loyalty. Our members will come through.”

*A version of this article appears in the April 27, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!